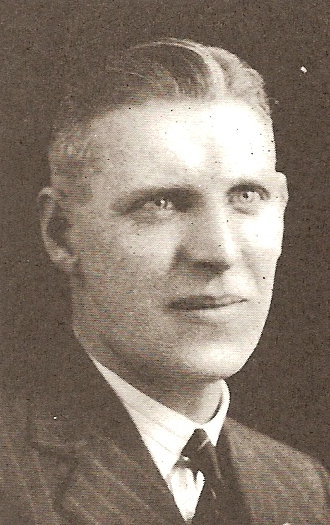

Hogan was born in Lancashire in 1882, six years before Celtic came into being. Born into an Irish family with eleven siblings, the diminutive figure became a giant on the European continent. Hogan dismissed what he saw as the ‘kick and rush’ style of English football which placed great emphasis on power and strength, rather than technique. He emphasized skill and technique over brute strength. He like Brian Clough many years later was a voice in the wilderness.

Being ignored in England he took himself off to continental Europe and there made his name. He coached the legendary Hungarian team which dismantled the England team at Wembley in 1953 by six goals to three. It wasn’t just the score line that stood out, but the manner of England’s defeat. They were comprehensively outclassed on the field, and the whole notion of tactical awareness was a novel concept to the land that gave the world football. Jimmy Hogan was central to this, and Ferenc Puskas the magic Magyar, testified to this when playing for Real Madrid. Helmut Schoen who managed the world cup winners of West Germany in 1974, also cited Jimmy Hogan as being a major influence.

When Kelly invited Hogan to coach at Celtic in the fifties he was already a very old man, but possessed by an almost missionary zeal he set about converting Celtic’s players to his cause. The likes of Charlie Tully who refused to be coached by anybody and dismissed the old man as a crank. Tully great player as he was, did not respond to being told what to do. However others did listen and learned, in particular the young Jock Stein who understood intuitively the message Hogan was trying to impart. Great emphasis was placed on ball control, retaining possession, tactical deployment and above all physical fitness.

These ideas seem quite normal by today’s standards, but way back in the early fifties they were revolutionary. Hogan’s ideas and methods were inculcated to Stein whose natural intelligence allowed him immediately to recognize their worth.

Kelly’s greatest decision was to appoint Jock Stein as Celtic manager which in itself was a bold move. The revered but ineffectual Jimmy McGrory was replaced by a man who had proved himself first at Dunfermilne and then Hibernian.

What sort of players did Stein inherit? It has to be said that the basis of the Lisbon Lions team was already there, but they were disorganized, demotivated and in a general state of disarray. Pat Crerand had been allowed to leave for Manchester United, but the vastly superior Bobby Murdoch replaced him after Stein made the inspirational decision to switch him from inside right to right half. In short, the players were already there under Kelly’s watch. He had the contemporary idea of finding, developing and retaining local talent. Willie Wallace and the veteran Ronnie Simpson would be added, but the nucleus was in place due to Kelly’s philosophy. The rest was up to the genius that was Jock Stein, Kelly despite the stereotype did not interfere in team selections. Kelly and Stein had a very amicable relationship based on mutual respect.

Kelly was very much a proud Catholic and equally proud of his Irish forbears. We can still see the black and white photos of him with numerous members of the Catholic clergy. He was determined that Celtic should never bow to the forces of ignorance and sectarianism that governed (and continue to govern) Scottish football. The current spat with Peat and co, were as nothing to what Kelly faced in the fifties and sixties. Glasgow and Scotland was much more polarized than it is today. Having an Irish sounding name or coming from a Catholic school meant automatic exclusion from the workplace. Rangers operated an open sectarian policy of recruitment, aided and abetted by those who ran the game. Many Catholics felt totally excluded from mainstream Scottish society. Outwith their faith and their families, Celtic football club remained the sole institution that championed the cause of the underdog Catholic population. The great flag dispute when Celtic were ordered to take down the Irish tricolour from the main stand due to its ‘provocative’ nature, was one of Kelly’s finest moments. He refused to be bullied by the bigots and the tricolour continues to flutter above Paradise.

Kelly remains a perplexing figure, on the one hand despotic and intransigent and yet on the other hand perceptive and receptive to new ideas. It was Kelly who sent the young Jock Stein to ‘observe’ the World Cup finals in Switzerland in 1954. There he saw Hogan’s protégés the mighty Magyars narrowly lose to West Germany in the final. When one reads of the input of Stein and to a lesser extent of Hogan, we see the genesis of the “Celtic way’ of playing football. The Stein/Kelly era was the definitive period when the Celtic way emerged. It didn’t happen by chance, it was created by Jock Stein and nurtured by Bob Kelly.

It was also Kelly who mooted the idea about Celtic joining the English league as far back as the late sixties. He also foresaw the coming importance of television revenue for football and its consequences. Kelly’s visionary outlook is perhaps an example for those running the show at Celtic Park in 2010.