The winter of 2011-12 was a momentous year for Celtic. Our rivals went bust. The only club in Scotland with the financial wherewithal and size of support to offer any meaningful regular competition for trophies, and specifically, the league had died. They had died ostensibly chasing the dream of domestic success and European competitiveness. A new version of the club was formed, adopting the same colours and logos, playing out of the same stadium and were allowed to enter Scottish football at the lowest tier of the professional league. As season 2021/13 kicked off, we therefore knew it would be at least four years before they would be able to offer any competition to Celtic. This afforded the decision-makers at Celtic Park a unique opportunity to lift their gaze above the weekly humdrum of domestic competition and view a horizon of European progress that would require medium to long-term planning and allow them to consider opportunities and give them the breathing space for decision-making that the necessity of finishing one goal ahead of another team negated.

There was one other event in that winter that was perhaps more seismic for Celtic and was certainly more important for a raft of clubs of a similar size or demographic nature to us and that was taking place just down the road in Manchester. As a tabloid would put it, it was a meeting of sport geeks and boffins.

Modelled on the MIT Sloan Conference in Boston, Sports bodies, football clubs and journalists were invited to a meeting by Manchester University to discuss data and statistics in sport. The lead speaker was the retail director of Tesco who detailed how the supermarket giant mined the information from their Clubcard clients become Britain’s number 1 supermarket.

Few in attendance would, at the time, appreciate the significance of that event. Indeed, it was attended by more journalists than football clubs. However, it has now gone on to become one of the most important and influential conference events in European football. And it set the stage for a transformation in attitudes of clubs of the size of Celtic and Ajax and Anderlecht and many others who would come to the fore of European football in the tier below the elite leagues over the next 12 years. But whilst many clubs of our size have understood what has taken place and embraced the changes set out and recommended at that conference, Celtic seem to have learned a different lesson in 2012, perhaps caused by the nature of the death of our biggest rival and we appear to have been struggling to understand and accept those lessons ever since.

Football revenue had changed dramatically in the 20 years prior 2012. We had seen the establishment of the Champions League format and the formation of the English Premiership. The success of both of these competitions had been driven by increasingly large TV contracts. And as the years progressed, the more the elite clubs got, the more they spent and the more they spent, the more they needed and the more they needed, the more they got and the more they got, the more they spent. Football inflation became rampant.

In 2003 when Celtic reached the UEFA Cup final, they were within top 20 clubs for income in European football and our revenues were up there with the top English Premiership sides. But already we were seeing the challenges, with Brian Quinn confirming at that years AGM that it had taken a UEFA Cup final to match the revenues of a Champions League group stage. That change in finances was starting to come through in the quality of player that clubs of the size of Celtic could attract. Whilst at the time of the Seville season, a top player at a club like Celtic could earn the same as most squad players bar the elite at a top Premiership team, by 2012 the wages on offer by Celtic or Sporting Lisbon or Ajax couldn’t usurp the offers being made to someone whose career would involve spending most of a season on the bench (if they were lucky) at an elite club at one of Europe’s big five leagues.

The top clubs at the non-big five leagues had a problem. Spending money and getting ever deeper into debt only for the gap between them and the big five elite to get bigger was not a viable long-term solution. The bills were piling up, but the scope for income was getting further away. Never was this more any evident that in Scottish football, where the country’s second largest club came up with one financial ruse after another, with investors losing their shirts and eventually getting to the point where the biggest shareholder decided that it should be the taxpayer who funds the team through an illegal tax-free player wage set up and eventually through the spiralling debts of these parent companies, which resulted eventually in a contributing factor to the biggest bank in Scotland going bust. Understandably, the Celtic board saw what was coming with their rivals and decided that spending to accumulate was not working. A different, more prudent model was required. We stopped our debt spiralling at £18 million our neighbours didn’t. Our neighbours went bust and we kept trading and kept winning.

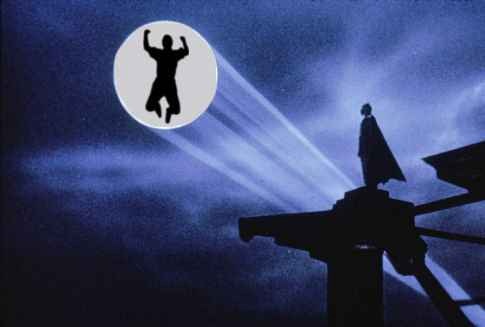

Those 10 years from the Seville season through to the death of our rivals is essential to understand when looking at the culture of the club today. For better or for worse, most of the current board and executives were at the club during that formative period. Moreover, the culture of the club and the financial prudence required to get the club through that period has been seared into the corporate culture at Celtic. My perception is that this corporate financial discipline that was essential to prevent us skipping down the route of financial peril that was encouraged by the bulk of the Scottish football media and saw many clubs follow the false prophet, or the Pied Piper of David Murray, down the route of financial ruin of the speculate to accumulate nonsense, has become so engrained into the fabric of our fiscal DNA that our existing executives are simply incapable of countenancing that any alternative is once again appropriate or viable.

That culture of jam tomorrow that was all pervasive throughout football and particularly in Scottish football, is most evident in the rules that surrounded the formation of the SPL. Shiny new stadia that, whilst it was essential to have new modern facilities for supporters, the 10,000-seat concept was a noose around the neck of clubs, many of whom have never recovered and some are only just starting to see light at the end of the tunnel.

As stated, it is tessential to put the context of the mindset of the Celtic executives and the corporate financial culture within the context of that glitzy spending culture that swept through Scottish football in the mid-90’s to late 2010s. The strength of financial discipline that would have been required to swim against that tide and decide when a debt hit £18m that enough was enough was immense. Unfortunately, the urge to ignore the ongoing desire in football to spend more this season than last and, with football inflation running at double or triple the rate of standard inflation during that period seems to have made our board myopic when it comes to the financial management of the club. With the daily grind of Scottish football, where the performance of Celtic is compared every minute of every hour of every day to the performance of one other club I believe a culture developed within Celtic that was difficult to break.

When people are up to their necks on the daily grind of business challenges, it can be difficult to spot when your industry changes. When you’re navigating across difficult terrain, the most important thing is to make sure that you remain sure footed and the next step keeps you upright. It can be difficult to pause and take moment to assess the horizon. It appears therefore, that the necessary fiscal discipline required during the 2000’s meant that when the moment arose to lift your gaze above that daily grind and plan long term the opportunity was missed.