Authority is a fragile concept, and football management epitomises this. Within clubs, authority is often steered by two sociological components – traditional authority and charismatic authority. In the case of Neil Lennon, he has successfully led the club via a fusion of the two. He has the habitual authority based upon the context of being appointed the manager and given a mandate to lead, but he also held a sense of authority because others wanted him to. This charismatic authority approach encapsulated the board, fans and players alike. The oft-quoted ‘bringing back the thunder’ has its roots in sociologist Max Weber’s argument, in that in order for some managers to truly shine, a ‘cult of personality’ must be created.

In his first full season, certainly from key events, there seemed to be a cult of personality surrounding Lennon, that had its roots in both his playing days, and his upbringing. The death threats showed the human side that was difficult not to both sympathise and strive to succeed for him. Fans bought into his approach, and his name was chanted. Player wise, seeing your manager publicly suffer must be a unifying event. This philosophy, however, can only go so far. The context of the opposition is also pivotal.

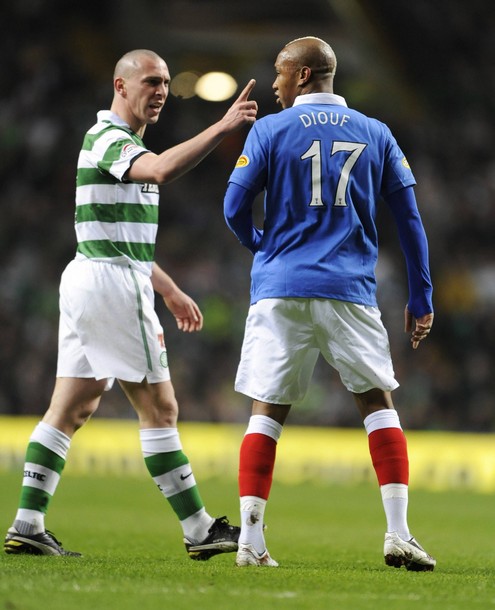

For Lennon’s first two seasons, there was a clearly defined enemy, one that, in many aspects, were as much to do with the identity of Celtic as the club itself. Countless arguments have been made about Celtic thriving without Rangers, but if we look purely from a competitive standpoint, these arguments are flawed. With the sheer hatred that manifested towards Lennon from fans of Rangers, the cult of personality was at its strongest. The accepted behavioural rules would be to counteract this with unparalleled support that met the hatred face to face.

Whilst Rangers may still exist in some form, they have no direct impact. Fans can still trade insults, but without an epicentre of conflict, conflict itself is merely verbal. There needs to be a focus, and without Rangers, the cult of personality takes a hit. In this regard, the Champions League was a poor substitute, as rivalry could not be manufactured. The success over Barcelona was a moment that history will never forget, but domestically, lack of rivalry leads to internal debate.

Amidst the plethora of off-field issues that Neil Lennon has had to endure, it is easy to forget that his domestic record, for a Celtic manager, is pretty poor. Realistically, he could have won eight trophies thus far. He has won two. Three Hampden defeats in a year is unacceptable, especially as the pattern seemed to replicate like a cheating partner. Yet, the underlying cult of personality leaves the notion of criticism a highly confusing one. Using the Barcelona victory as a baton to beat away criticism of domestic form is both naïve and insulting. An Inverness supporting friend maintains the argument that Neil Lennon (and Ally McCoist) would not succeed at any other club. He thrives in the environment due to his past and his personality.

Of course, an apathetic domestic campaign is not purely the fault of the manager. Whilst I firmly believe he is guilty of struggling to motivate the players in certain matches, the players themselves are also in a confused conundrum. An article by The Guardian’s ‘secret footballer’ in September 2012 suggested that footballers would much rather qualify for the Champions League than win a trophy. A medal is merely a piece of sentimental silverware, but playing in the Champions League means higher wages and bonuses. The piece went on to quote Craig Bellamy, who said that he has no idea where his 2005 Scottish Cup winners medal is, and that trophies do not motivate him in any way.

Perhaps this is the root of the domestic malaise. Is there a feeling of performing to the bare minimum, knowing that this is still enough to succeed in the league? A parallel is a first year at university. At most places of further education, your first year is simply judged a pass or a fail, with grades not carried over to the latter years. Hence, you can start off well, and then coast along with the safe feeling that passing is an inevitability. The problem starts when the second year carries greater scrutiny. For Celtic, the cups are this second year, because coasting along can see elimination, as was the case against Kilmarnock, Hearts and St Mirren.

Without a Rangers team for the next two years, will the domestic form continue to frustrate? Celtic’s biggest concern could arrive with no Champions League football. This year’s campaign was either the start of an engaging new beginning for the club, or something that hid a wider problem. If there is no Champions League campaign and no identifiable rival that can serve as a motivational tool, then there are still targets. A domestic treble is feasible, and a Europa league run would be geographically if not financially stimulating. Being motivated because you are paid large sums of money sometimes is not enough, and not just in a footballing context. The manager has a pivotal time ahead of him, and the events of the next fifteen months will truly define Lennon’s Celtic legacy.