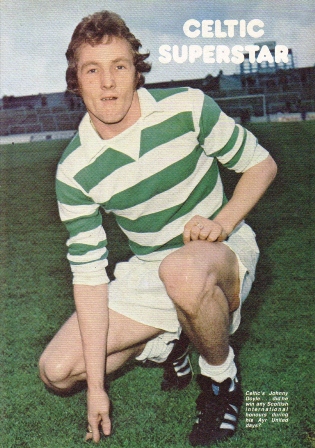

On August 30th 1980 Celtic found themselves in a pickle against Stirling Albion at Celtic Park. They had lost the first leg of the League cup tie 1-0 at Annfield and were drawing 1-1 in injury time when Tommy Burns fired home a dramatic equaliser. The game went to extra time and at last Billy McNeill threw the young Charlie Nicholas into the fray and Celtic ran out winners by 6-1 with Charlie scoring twice. He had made his mark and was here to stay.

During September and October 1980 it seemed as if Nicholas couldn’t stop scoring. He became the darling of the press, was a headline writer’s dream and the nicknames came thick and fast ; Charlie Bubbles, The Cannonball kid, Charles De Goal, Saint Nicholas and the rather obvious – Bonnie Prince Charlie (That‘s enough nicknames – Ed). Around this time I recall he did a photo shoot for the Evening Times where his clothes were provided by Ger-ralds, a rather expensive, trendy, clothing boutique at the corner of West Nile Street and Sauchiehall Street. As a teenager I found this an exciting innovation as Charlie smiled from the newspaper in his fashionable attire, with the modern fad of wearing no socks under his shoes, for which Billy McNeill was to often punish him financially. My Dad, however, raised an eyebrow in disapproval, not necessarily because of the fashion of the day, although goodness knows he and I would have some run ins on our own on that front in the years ahead, but his objection was that Celtic players should not behave in this way. They were not pop stars or movie stars, they were ‘real’ men and they should not act in this manner. But the horse had bolted and Nicholas paved the way for a generation of playboy types like Johnston, McAvennie, McCoist and the like, who would all take this ‘footballers fashion’ lark a bit further, often to the detriment of their performances on the park. Somehow you couldn’t imagine Jimmy Johnstone or Kenny Dalglish doing anything similar in previous times or Jock Stein even tolerating it.

Despite all that, it has to be said that Nicholas was the most outstanding young player to have came on the Scottish scene since Kenny Dalglish. He had wonderful touch, great vision for one so young, a shot like a mule with both feet and an uncanny knack of finishing in a cool fashion. In short he was the most exciting young talent in the game at that time. The only asset he lacked was a turn of pace and had he had that he would have been the perfect striker. He developed a magnificent partnership with Frank McGarvey and with Frank’s help he became the top goalscorer in the Scottish game and one of the best strikers in the UK.

Charlie’s start in a Celtic jersey was a terrific one and the honours began to flow but tragedy struck in January 1982 when he badly broke a leg at Cappielow in a reserve game after an accidental clash with Morton defender Joe McLaughlin. It was to take him six long months to get back to full fitness and the injury was to make Charlie a changed man. By August of 1982 he was into the last year of his contract. Celtic, led by the old, conservative chairman Desmond White had still not fully come to terms with the freedom of contract issue which footballers now had available to them since 1980. Basically, Nicholas had clicked that he could leave the next summer on freedom of contract with a transfer fee to be decided by a tribunal and as he was probably the first ever Celtic player to command an agent there would be siren calls all around him. Whether old Dessy had cottoned on to this was anyone’s guess. But as the months went by Charlie scored a barrel load of goals in a successful Celtic side at home and in Europe (he would score 48 in total) and the club were slow to make an offer. It was clear now that the English would come calling especially after he scored an outstanding goal for Scotland on his debut against Switzerland.

After New Year 1983 it became like a circus. A swarm of media men from television, radio and newspapers, would come North with only one thing on their mind, to unsettle the still-young Celtic star. Each Saturday lunch time you could tune into the Saint and Greavsie show on ITV which would show Nicholas’s latest goals (from ‘chilly Jocko-land’ as they referred to it) and the old nauseous alcoholic (Greavsie) would entice Charlie with the Cockney-ese message – ’C’ahm Sarf yang man, c’ahm Sarf Chah-lee’ or words to that effect.

Towards the end of that season the unrest around his contract unsettled Celtic badly. Another title was thrown away this time in the direction of Tannadice although Celtic had the dubious pleasure of humping Rangers 4-2 at Ibrox with four second half goals in his last game, Nicholas scoring from two penalty kicks. At the end of the game he ran behind the Celtic fans to wave his goodbyes although it was another 10 days before he would announce his departure publicly.

Liverpool, Manchester United and Arsenal chased his signature and he spoke to all parties. At this point it should be noted that this was not the Arsenal of Arsene Wenger or even of George Graham. This was an Arsenal who would line him up in due course with such luminaries as Raphael Meade, Ian Allinson and Perry Groves. Hardly names that trip off the tongue when recalling the great players of the day.

At the point of his departure Celtic fans were confused and angry. Confused that a self confessed ‘Tim’, one of their own who stood in the Jungle in 1979 during the 4-2 game with other young Celtic players in jerseys nicked from Neilly Mochan’s kit room, should want to leave after only one full season in the first team. He had only turned 21 years old and owed Celtic a wee bit more before any departure a la Kenny Dalglish, who gave the club seven great seasons and was an experienced player when he departed the Celtic scene. But two things swayed Charlie’s decision. Firstly the broken leg 18 months earlier had cast doubt in his mind that his career could end anytime and as such he should make the most of it which is clearly understandable. Secondly, in rejecting the overtures of Anfield and Old Trafford he did not move for football reasons but for the bright lights of London in which he could attend the big city night clubs such as Stringfellows each week, in his trendy black leather trousers, where he had become something of a celebrity.

On a professional note there were a lot of older, wiser Celtic fans at that time who admired the partnership of Nicholas and McGarvey but who noted that wherever Nicholas went he would need a similar player to McGarvey who would do the leg work and be able to take the brunt of the physical challenges that came from big defenders. Arsenal had no one of McGarvey’s ilk at Highbury and Charlie’s career plummeted. Four years later he found himself at Pittodrie in an Aberdeen side who were on the wane after Fergie’s glory days of the early 1980’s and who were the only side to offer him a passport from his misery in London but he would not be in the North for long. It was no secret that Billy McNeill, who was himself in his second stint at Parkhead, wanted him to return and in the summer of 1990, Charlie the prodigal son returned. He was never the quickest on the field but he looked overweight throughout his second spell as a Celt and was injury prone to boot. The years had caught up on Charlie. The fresh faced, boyish good looks had gone and when he tried his hand at designer stubble he just looked scruffy.

In his second spell at Parkhead he did come up with some wonderful moments in what was an otherwise disappointing home coming. In March 1992 he summoned up two sublime goals which will forever be remembered by those who saw them. On March 21rst he opened the scoring at Ibrox in a 2-0 win, when he took a long ball from a Chris Morris free kick and volleyed home a ferocious shot past Andy Goram in the Rangers goal, a spectacular effort hit with great technique. A week later on March 28th he ran across the Dundee United defence 25 yards out with no danger apparent and suddenly chipped a glorious effort passed the bemused Alan Main who never moved an inch. They were both goals of the highest calibre and only a truly great player could have scored them. But these rays of light were few and far between.

Charlie was a constant during the unsettled period of the early 1990’s but when Tommy Burns arrived as manager in 1994 his days were numbered and he couldn’t hide his disappointment at being left out of the 1995 Scottish Cup final against Airdrie and so Celtic released him and he moved on for the last time.

Charlie Nicholas the player is fondly recalled but Charlie Nicholas the man is maybe not and there are instances that can be cited in support of this. They say politics and sport should not mix and this was definitely the case in 1984 when Charlie appeared at a televised celebrity Conservative rally organised by Kenny Everett in support of Margaret Thatcher and the Tory party. This was one of the few occasions where Old Firm fans came together, united in hate of the then Prime Minister, as the West of Scotland’s industries and economy lay ravaged by Conservative policies. He later claimed he did not know anything of the event he was attending which either makes him very naïve or very, very stupid. You pick.

Years later Jack McLean absolutely lambasted him in his Glasgow Herald column when Nicholas closed his Café Cini Glasgow hostelry for a fortnight, for renovation work, and informed the bar staff they would not be paid during this period. Many of the workers were young girls who were single parents and McLean commented that he knew his father, Chic Nicholas from old, who was a notable trades unionist, and Jack pondered that one could only wonder what old man Nicholas thought about this stunt.

In more recent times Charlie dropped a faux pas on National television when he and the odious Jim White were heard to make derogatory remarks against the ‘Fields of Athenry’ song in a TV studio, which was heard being played over the loudspeaker at Celtic Park before a big European game. So much for Charlie the Celtic man.

A friend of mine swears blind to this day that he saw Nicholas ‘tired and emotional’, as they call it these days, in a City centre bar the night before the Scottish Cup semi final against Aberdeen on 16th April 1983. What can be said for certain is that he, inexplicably, did not play the next day and Celtic lost a big match 1-0 in the process and the cause of his absence has never been fully explained until this day.

Nicholas ended his career at Broadwood with Clyde and even then left in controversy. Clyde were paying him the princely sum of £1000 per game, a considerable amount of money to such a small club, and in mid season he announced that he could not motivate himself to play in front of small crowds any longer in the lower divisions. Most professionals will tell you that the day you stop playing is the worst day of their profession and yet here was Charlie unable to sustain his interest even for the love of the game at the end of his career.

In recent times he has become a pundit on television and it’s sometimes difficult to separate the real Charlie from the hilarious spoof impersonation that Jonathan Watson performs so well. However these days he seems to be an arch critic of all things Celtic and he seems to have a grudge against Peter Lawwell in particular judging by recent press reports. Peter has nothing to worry about because, intellectually, criticism from Charlie Nicholas is the equivalent of ‘being savaged by a dead sheep‘, as a famous politician said once upon a time.

As I said at the start of this article Charlie Nicholas evokes many emotions in the Celtic fan but the over riding one will always be disappointment which is a shame because just think how good he could have been had the circumstances been different.