On February 20th 1980, a huge crowd of 27,166 crammed into the compact Love Street ground with kick off held up for fifteen minutes as fans struggled to gain entrance. Celtic had been fortunate to gain a replay just four days previously, when a last gasp Murdo MacLeod goal was required to keep them in the competition.

Thousands of fans impatiently queued outside, whilst inside the ground, spectators climbed perilously on to floodlight pylons to gain a better view of the proceedings. The lucky ones gained entry, for there were thousands of supporters locked outside when the police insisted on closing the turnstiles for safety reasons, shortly after the kick off.

St Mirren started brightly, and could have scored before Jimmy Bone got the opener in eleven minutes, when his looping header from a Lex Richardson free-kick found the net, before Celtic were dealt a huge blow.

In 18 minutes, Celtic defender Tom McAdam, and St Mirren striker Frank McDougall, clashed off the ball, after McAdam cleared the ball upfield. After consulting the far side linesman, referee Ian Foote elected to book McDougall but chose to send off McAdam, which was a most controversial decision.

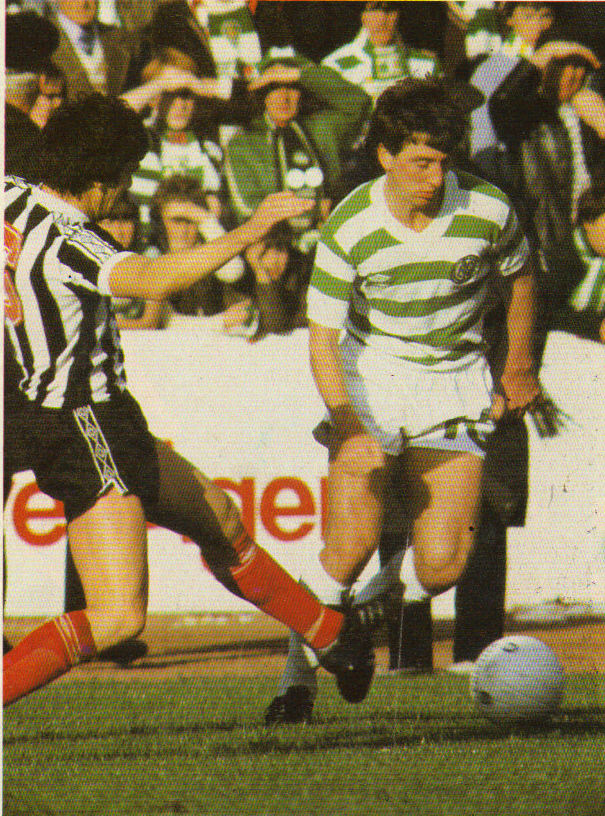

Despite being a man short, Celtic players now showed an increased sense of urgency, and the Celts equalised on the half hour. George McCluskey cleverly beat an opponent, and his through ball sent John Doyle clear on goal. The Celtic forward cleverly feinted to shoot, allowing keeper Billy Thomson to make his move, before calmly placing the ball past him into the net and Doyle milked the adulation of the fans behind the Love Street end goal.

Controversy reigned again in the 59th minute, when Peter Weir appeared to stumble after a Davie Provan challenge in the area. Ian Foote had no hesitation in giving a penalty, despite the protests of the aggrieved Celtic players. Peter Latchford was almost the hero after he saved Doug Somner’s initial attempt from the spot, but the Saints man kept his composure and slotted the rebound to put his team in front.

Celtic’s sense of injustice burned deep inside them, and the players now increased their efforts to get back on level terms. Celtic were awarded a penalty of their own after Provan and Doyle worked a short corner, and as Doyle raced into the penalty box, Weir sent him crashing to the ground. The veteran Bobby Lennox showed commendable coolness, placing his penalty calmly past Thomson at the Caledonia Street end, to force the game into extra time.

The additional period had barely started, when Doyle again took a hold of proceedings. He raced clear from the half way line, knocking the ball one way past a defender, running round the other side of him. McCluskey was in an offside position, and had he moved towards the ball he would have been flagged, but he stopped to allow Doyle the chance to chase after his own pass. As Thomson came out from his goal, Doyle went past him, but knocked the ball too far ahead. He then retrieved the ball on the bye line, just before the ball went out of play, with Thomson back on his line and the Saints’ players racing back. Showing great quickness of thought, Doyle looked over as if to cross, only to turn and hammer the ball at Thomson, at his near post. The Saints’ keeper was taken totally by surprise, and the ball rebounded off him and into the net.

Some observers commented that Celtic had played as if they actually had twelve men, rather than a reduced ten, and St Mirren now looked a broken team. At the end of the game there was much celebrating from Celtic players and fans, with two goal hero Doyle’s name being sung loudly in praise.

This was one of Celtic’s greatest cup victories and the following tribute from the Evening Times perhaps best sums it up the mood that night:

They should have filmed this Scottish Cup replay in glorious Cinemascope for it was another mighty epic of searing endeavour, raw courage, a tremendous fight against the odds and heart stopping action. Celtic took all the Oscars in sight and their 3-2 victory at a Love Street, which seethed and shook like an earthquake for one hundred and twenty pulsating minutes, will go down in history as a supreme example of what makes a club great.’